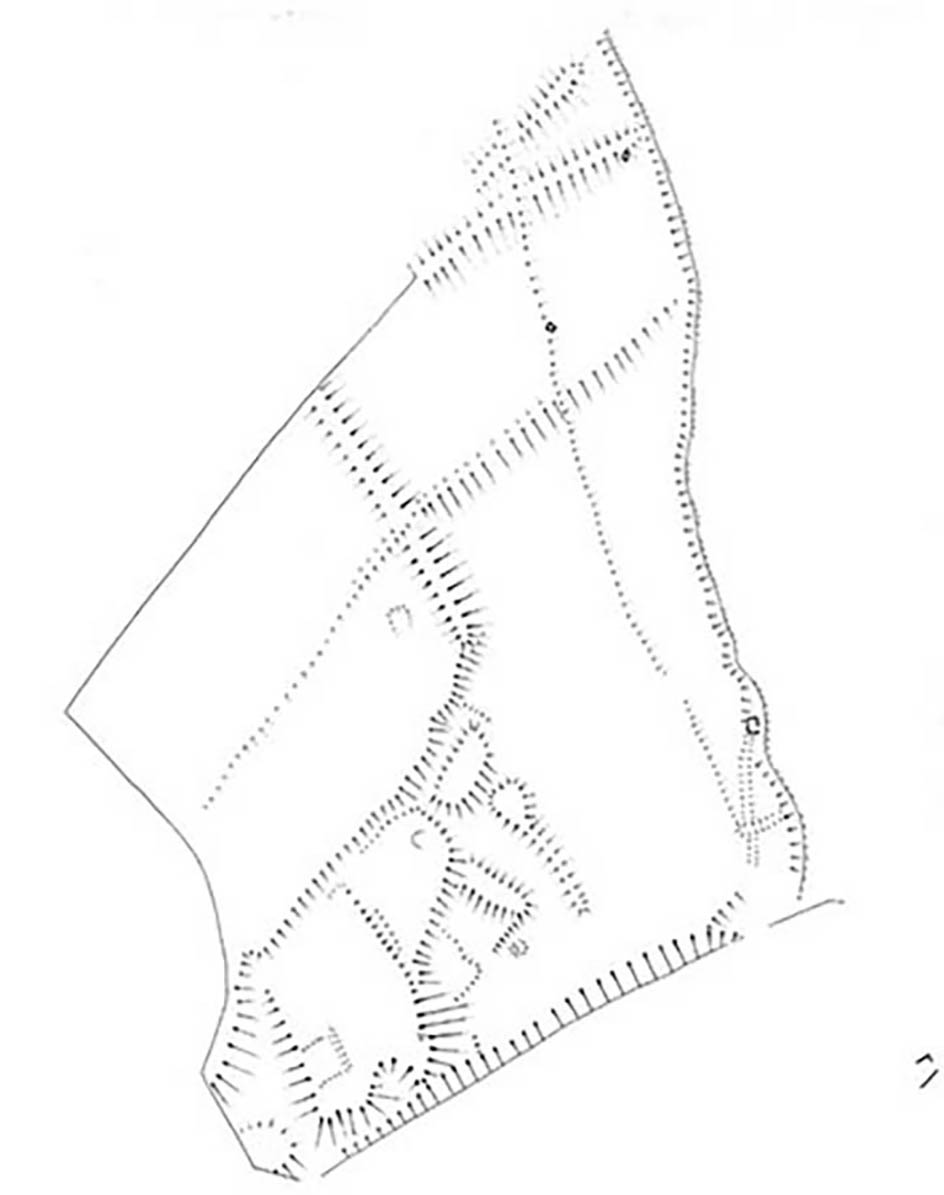

earthworks north of the church |

For many years the group of earthwork features in the field to the north of the church had been believed to have been the traces of a deserted medieval village (DMV in archaeological parlance). In 1970 archaeologists of the Archenfield Archaeology Group, led by Norman Bridgewater, excavated a trench across part of this area. The Archenfield Archaeology Group had been established in 1961, and by this time had conducted a number of successful field projects, particularly in the Romano-British industrial town of Ariconium and of a Romano-British villa-like building at Huntsham, a few kilometres south of Hentland. At Hentland the group soon recognised that what they were seeing was not a deserted medieval village, as had been long assumed, and was the reason that they were excavating there. The earthworks, the team concluded, were the remains of old quarries, excavated for the extraction of the good qualiy sandstone which here lie not far below the ground surface. Having ascertained the nature of these features, the group rapidly moved on to excavate a site on the opposite, southern, side of the church, where they found the foundations of a medieval house. |

alidade and plane table survey |

In 2006 volunteers on the Landscape Origins of the Wye Valley project participated in an alidade and plane table survey of the Hentland earthworks. An alidade and plane table is a simple but accurate method of surveying earthworks, and has been used by archaeologists for many years. The survey was conducted without any knowledge of the Archenfield Group's findings of 35 years earlier, as in those days negative results were often not published, and it was only as a consequence of a discussion with one of the surviving members of the group that the results of the machine trenching of the site were discovered. |

the completed plan of the earthworks |

Stone suitable for building purposes is widely distributed in England and Wales but medieval transport was extremely costly and so sources of stone as near as possible to the building were sought. Even when quarries were very close to building sites transport costs might be very high. In 1278-80 the quarriers at Edisbury in Cheshire who dug the stone for Vale Royal Abbey four or five miles away were paid £104 while the carters who transported it to the site were paid £347. Cost considerations could lead to inferior stone being used if it was available near the site. Medieval quarries could be quite small. The Oxford Dominicans operated one of 100 feet square. A quarry at Headington for Merton College measured 20 feet by 40 feet. A quarry at at Norton, Somerset was originally just 20 feet each way. Nor need the quarries to have been deep. Headinton quarrymen dug down 7 or 8 feet for the stone for Merton College in 1449. The overwhelming majority of village churches within the area of Silurian Raglan Mudstone Formation (part of the Downton Group) and the Early Devonian St Maughans and Brownstones formations (the rock beneath Hentland) are built from local stone. A common method of operating medieval quarries was for those responsible for the erection of a building to open up and operate the quarries themselves. A quarry almost immediately adjacent the building would simplify the whole process. Until the 19th century quarries were often opened up on an ad hoc basis - a farmer might have just enough stone dug for a single building. A caveat is that a seam of the best stone, once identified, was often quarried away entirely - until that seam was entirely exhausted. Medieval transport was very expensive and building stone was sourced as locally as possible. In 1231 permission was granted for Lincoln cathedral to quarry stone in the ditch of the castle at the other side of the market place; 150 metres away. The local sandstone is a freestone, so named because it can be freely cut in any direction, fine-grained, uniform and soft enough to be cut easily without shattering or splitting. As a working hypothesis, it is suggested that the most likely purpose of this quarrying was to provide stone for building the church. Subsequent work could utilise stone from further afield as transport costs declined. |